“As the different streams, having their sources in different places, all mingle their waters in the great sea; similarly, the different paths which men take through different tendencies, however divergent they may appear, crooked or straight, all lead to Thee, O Lord.”1 – Sanskrit Hymn

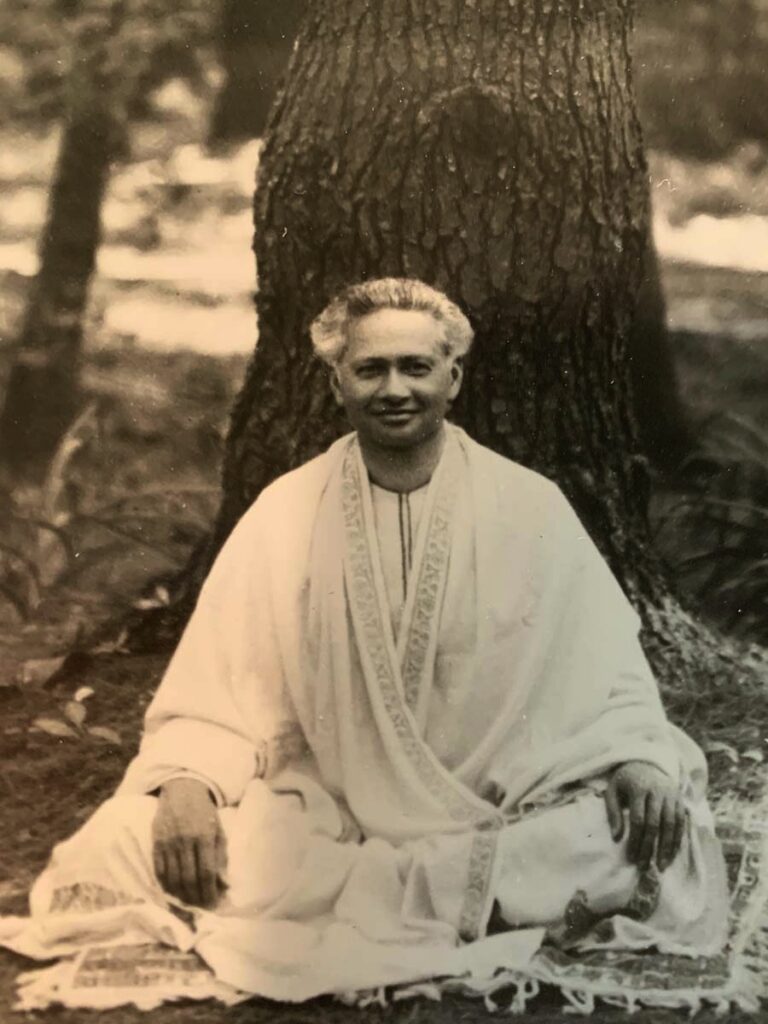

Swami Paramananda (1884-1940), a disciple of the great Swami Vivekananda and member of the world-renowned Ramakrishna Order, was a prolific author, poet, teacher and mystic. He was instrumental in bringing the philosophy and teachings of Vedanta to the West from his native India in the early years of the 20th century. The Swami worked tirelessly throughout his life spreading the message of Vedanta and encouraging people to find their true spiritual nature and connection to the Divine through their chosen Faith. He was a genuinely humble man and model of spiritual wisdom and enlightenment. People of all faiths who met him, loved him for his wisdom, character and devotion to God.

Swami Paramananda’s Principles and Purpose of Vedanta, though written a century ago, offers timeless wisdom of the Vedas in a format compatible with the language of Western culture. He wrote with clarity and precision during an era when very little was known about Vedanta and the Hindu religion in Western culture. Following is an excerpt of Principles and Purpose of Vedanta, reprinted here with permission from Vedanta Centre Publishers in Cohasset, Massachusetts.

Vedanta and Its Origin

Vedanta comes from two Sanskrit words, Veda (wisdom) and anta (end), and means “end of wisdom” or supreme wisdom. It is the name given to the teachings of the Vedas, which have been handed down to us from time immemorial. The special feature of Vedanta is that it is free from all sectarian and exclusive ideas and for that reason it has infinite scope for tolerance. It is not based on any personality, but on principles; therefore it is the common property of the whole human race. Sincere study likewise enables us to recognize that all the noble moral and spiritual teachings of the Greek, German and other Western philosophies are neither new nor original, but are to be found in Vedanta; because Vedanta itself is the revelation of the fundamental principles of the universe.

It springs, not from any human, but from a divine source. It represents no special books or doctrines, but explains the eternal facts of nature. It stands as the record of the direct spiritual perception of the ancient Rishis or Seers of Truth, who were not the founders of a religion or philosophy, but the revealers of the eternally-existing laws of the universe. As the law of gravity did not originate with Sir Isaac Newton, so also these laws did not originate with the Rishis, but had existed from the beginning of time and undoubtedly been discovered by previous Seers of Truth, for the Vedas as we know them are full of references to still earlier authorities. Thus we see that the principles of Vedanta run in parallel line with creation itself; and as creation is eternal, so are these principles.

Conception of God

As the source of all these principles Vedanta recognizes one Supreme Being, one law, one essence, whom sages call Satchidanandam, “Existence – Absolute, Knowledge – Absolute, Bliss – Absolute.” Out of that one substance comes the manifestation of these manifold phenomena. “He is the thread on which the different pearls of various colors and shapes are strung together.” God the Absolute is this thread or essence. He dwells in the heart of every being as consciousness; from the minutest atom to the greatest of mortals, He is present everywhere. In Him we live and move and have our being. Without Him there cannot be anything. He is one without a second. There cannot be more than one infinite Being, since infinity means limitless, boundless, secondless. Such is the Vedic conception of God, and the realization of this God is the ultimate goal of its teaching.

God Personal and Impersonal

Although the Supreme Being is one, He appears before us in many forms. As it is said in the Rig-Veda, “Truth is one, wise men call It by various names (and worship It under different forms according to their comprehension).” Herein lies the secret of tolerance, which constitutes the special characteristic of Vedanta. An Infinite Being must have infinite paths leading to Him. These infinite names, forms and paths are to suit the varying tendencies of His innumerable children. Therefore He is sometimes personal and sometimes impersonal. Those who seek to realize Him as an impersonal or abstract ideal, following the path of philosophic discrimination, see Him in the Self and the Self in all beings. Through this they transcend all human limitations and find absolute peace and bliss in oneness.

“When the knower of Self finds all beings within himself, how can there be any more sorrow or delusion for him who sees this oneness.” (Upanishads).

To those who cannot follow the abstract ideal, He appears as a personal God, a God of infinite love, infinite beauty, the source of all blessed qualities. With these He establishes the personal relationship of loving Mother, loving Father, Child, or Friend; and one who sincerely strives through this path of personal worship with true love and devotion also attains the realization of the Supreme. For it must always be remembered that the worship of the personal or impersonal takes us to the same goal. “Whoever comes to Me (the Lord) by whatsoever path, I reach Him. All men are struggling through paths which ultimately lead to Me.” (Bhagavad-Gita).

Man’s Relation to God

According to the teaching of Vedanta, this realization of God, or at-onement with Him, is the aim of human life; nay, it is our birthright. Forgetfulness of our true nature of Godhood is the source of all misery. There is no real difference between Jivatman (individual self) and Paramatman (the Supreme Self), except that the individual has taken a covering of limitations on him in the shape of name, form and various qualities, while the Supreme Self dwells beyond these. It is the same conscious spirit which exists in both; only in one case it shines partially, owing to limitation, and in the other it shines fully and freely. So when through purity and wisdom man finds his real Self, then this veil drops off and man and God become one and inseparable. “The knower of Brahman (Truth) becomes one with Him;” or as Jesus said, “I and my Father are one.”

This relation of man to God has been clearly set forth in one of the Upanishads thus: Two inseparable birds of golden plumage are sitting on the same tree; one eats the fruits of the tree, sometimes sweet, sometimes bitter; the other, not tasting the fruit, sits above as witness, calm, majestic and merged in his own glory. So the Jiva (individual elf) and God (the Supreme Self) are sitting on the tree of life. The Jiva, after tasting the different fruits of experience, both sweet and bitter, and grieving over his own impotence, becomes bewildered; but when he looks upon the other bird – the Lord, beholds His mightiness and realizes that they are really one, then his sorrow and delusion pass away. This vision of the Self removes all sense of duality and the One shines alone as the infinite, omnipotent Being.

Man can never be robbed of this divine birthright. No amount of wrongdoing can ever destroy it. His misdeeds may cause delusion and make him suffer, but after going through many experiences, both sweet and bitter, he is sure at last to find his divinity and be freed from all bondage.

Law of Karma

Though we all possess the same germ of divinity within us, yet we are not all equal. What is the cause of this inequality? Why is one born happy and another miserable, one intelligent and another dull? The difference lies in the degree of manifestation or unfoldment of the same divine power, which makes one great in wisdom and enables him to go through the varying conditions of life with courage and serenity, while another, whose mind is veiled, constantly makes mistakes and suffers. God does not send happiness to one soul and grief to another arbitrarily. “The All-pervading One partaketh neither of the evil nor of the good of any creature. Wisdom is covered by ignorance, thus mortals are deluded. “

The Hindus do not blame an invisible Providence for all the suffering in this world, but explain it through the natural law of cause and effect. If a man is born fortunate or wretched, there must be some reason for it; if therefore we cannot find the cause for it in this life, it must have occurred in some previous existence, since no effect is possible without a cause. All the good that comes to us is what we have earned through our own effort; and whatever evil there is, is the result of our own past mistakes. As, moreover, our present has been shaped by our past, so our future will be moulded by our present. This brings great hope and comfort, since what we ourselves make, we can also unmake. Therefore, instead of grieving over our past mistakes, if we direct our present energies with whole-hearted earnestness towards counteracting the results of past actions, we can make our future better and brighter.

This is the law of Karma, which in accounting for all the inequalities among human beings on natural grounds, does not make God partial or unjust.

Reward and Punishment

The idea of reward and punishment also springs from this law. Whatever we sow, we must reap. It cannot be otherwise. An apple tree cannot be produced out of a mango seed, nor a mango from an apple seed. If a person spends all his life in evil-thinking and wrongdoing, then it is useless for him to look for happiness hereafter; because our hereafter is not a matter of chance, but follows as the reaction of our present action. Similarly a man of virtuous deeds must reap as their result happiness, which none can take away from him. The nature of sin, which may be defined as the sum total of all our unkind and selfish thoughts and deeds, is to make the veil which separates us from God thicker. The nature of virtue is to make this veil thinner and thinner. And since God is the source of all bliss, the one must inevitably bring physical and mental suffering while the other must bring peace and joy.

We should, however, never lose sight of the fact that all these ideas of reward and punishment exist in the realm of relativity or finiteness. No soul can ever be doomed eternally through his finite evil deeds; for the cause and effect must always be equal. Thus we can see through our common sense that the theory of eternal perdition and eternal heaven is impossible and illogical, since no finite action can create an infinite result. Hence according to Vedanta, the goal of mankind is neither temporal pleasure nor pain, but Mukti or absolute freedom; and each soul is consciously or unconsciously marching towards this goal through the various experiences of life and death.

Reincarnation

The theory of evolution is entirely based on the law of Karma, for it is evident that something cannot evolve out of nothing. This law also offers a satisfactory and logical explanation for all the physical and mental tendencies which we have at birth. Whenever a man is born with any extraordinary power and wisdom, know that he possessed it even before coming into this body; because we do not acquire any power or quality accidentally, but all our knowledge and ability are based on past experiences or series of causes. So also is it with one who from his very birth is devoid of proper physique or intellectual faculties.

According to the theory of Reincarnation every soul passes through the various experiences of birth and rebirths until it attains its original perfection. Each time a soul is born here it brings with it the fruit of all its previous existence, which determines its character and environment in this life. Since these are the result of a man’s own effort, it cannot be said that he inherits his virtuous or vicious tendencies from his parents, but souls are drawn to that environment which is in accordance with their merits and best suited for their growth. As furthermore like attracts like, so we often find children and parents resembling one another.

Vedanta recognizes that the theory of evolution is not complete if confined only to material phenomena. It must also extend through the higher realms of man’s spiritual consciousness. Each individual has within him the germ of perfection, which does not reach its full unfoldment with the attainment of a human body or in one life-time. Therefore it is necessary for the embodied soul to continue to evolve through manifold experiences of pleasure and pain until this germ has reached its full manifestation of spiritual consciousness. The object of our coming into human life is to gain self-knowledge and when that is attained the bond of slavery breaks forever, man becomes divine and does not have to come here again like a slave. The theory of Reincarnation, as we thus see, is nothing more than the theory of evolution carried to its logical conclusion.

Immortality of the Soul

The immortality of the soul is another fundamental principle of the Vedanta philosophy. The Self of man is not subject to change, nay, it is birthless and deathless. Birth, death and all that lies between have to do only with the physical body, which has beginning and must necessarily come to an end. They do not touch the soul. “The Self is not born, neither does It die, nor having been does It cease to exist. Unborn, eternal, unchangeable, ever-existent, It is not destroyed when the body is destroyed” (Bhagavad-Gita).

Body decays, but not the soul, which only dwells within the body and permeates it with life and consciousness, but which is not tainted by any bodily action or condition any more than the sun is affected by the dust-covered window through with it shines. For a true Seer the body is only a dwelling-house or an instrument which he uses for the attainment of his original state of God-consciousness. Death is nothing but going from one house to another, until the soul has freed itself from attachment to ephemeral things and gained its release from the bonds of Karma. Karma has no power over the real Self. It binds only the apparent or external man, who identifies himself with nature and thus comes under the law of action and reaction or cause and effect. Through wisdom alone the individual can transcend this law and rise above the dualities of heat and cold, pleasure and pain, and realize his immortal nature.

The idea of immortality necessarily presupposes our pre-existence, since eternity cannot extend in one direction alone. It is evident that that which has no end can have no beginning. As this present life will be a pre-existence for our future life, so in the same way, the present must have been preceded by other lives. The Self is always the same in past, present and future; but only when our heart unfolds, do we perceive Its everlasting glory and thus conquer our last enemy, death.

….

The final pages of Swami Paramananda’s Principles and Purpose of Vedanta explain Yoga from the perspective and teaching of the Vedanta philosophy, as well as the universality of Vedanta. Book credits can be found on the Citations page of this website.

1Swami Paramananda. Principles and Purpose of Vedanta. The Vedanta Center, 1937. 31-32